Hi, everyone!

A month has passed since the last report. How time flies, almost unnoticed! I often feel aging has the effect of accelerating everything that is happening around us. Do you agree? Is that my illusion?

A friend of mine said to me one day: "A child of five years may see the coming year as a long period as this length of time corresponds to one fifth of the entire period he/she has ever lived. It is a considerable percentage."

If his argument is correct, the rate at which time passes subsequently will seem to accelerate...

Anyway, recently, I have been increasingly convinced that every day should be lived like an unrepeatable opportunity.

In the last report, I wrote something about maneuver training on the T-38 jet, although there was insufficient space for my description. I will now continue the interrupted portion, focusing on my in-flight experience.

The T-38 training jet can fly at ultrasonic speed if the onboard pilot wishes. However, since the cost of travel at such speed would far exceed the budget, normal training missions are limited to about 80 % of sonic velocity, roughly 850 km/h depending on altitude.

The fuel tank is full at the beginning of a training mission. Even with the tank full, the training duration must be limited to ninety minutes to allow a portion of reserve fuel to be retained for unexpected emergencies. With the limited "extra" fuel, the trainee must check the current weather at the destination. Frequent checking means the pilot will have more options available, even if the actual weather conditions subsequently decline to a greater-than-expected extent.

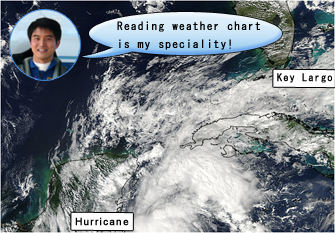

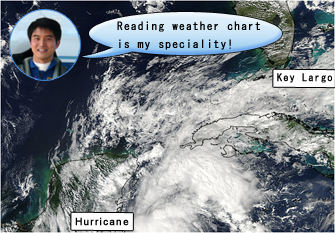

During NEEMO training in which I once participated, like Astronaut Yui, my knowledge of meteorological charts was very useful for me. The above photo shows the meteorological conditions of an eastern area of the U.S. during the NEEMO 15 mission, on October 26, 2011.

During ordinary training flight missions, the trainee flies toward an airfield one hour or one and a half hours away, where he/she lands and takes off if the remaining fuel permits.

It takes up to one hour to refuel the aircraft and ensure it is ready for takeoff and return to base.

In the mission that day, the cumulative flight duration over a total of 4 sections exceeded 5 hours. It was dusk when I returned to the Ellington Field.

Before I became an astronaut, I was working as a passenger aircraft pilot. There are several differences between the T-38 and the airplanes I used to maneuver, primarily the fact that only pilots are on the training aircraft.

This is a significant difference and means it doesn't matter if the aircraft shakes or undergoes rough maneuvers since no passenger will complain. A passenger aircraft carries hundreds of customers. Food and hot drink are served frequently and passengers may walk around to have access to toilets. Any "jerking" movement of a passenger aircraft without warning may result in severe injuries or burns. Pilots on passenger aircraft are very careful to ensure smooth flight. Pilots on board a T-38 feel much more relaxed, and less concerned about comfort.

Flight on a T-38 has other challenges, primarily the lack of any autopilot, which is provided on passenger aircraft and which allows them to be maneuvered automatically for everything except takeoff, which means passenger aircraft pilots can take more care of many other things. The non-automated T-38 must be constantly maneuvered with the control rod alone for about 90 minutes, with the pilot remaining on alert for any slight change of attitude, in order to maintain the required course and altitude.

Besides, the T-38 pilot has many things to do other than aircraft maneuvering and weather checking: checking the aircraft's current location on the map, operating a number of devices, reading charts and maps, and communicating with the control authority. It is hectic immediately after takeoff and during landing.

Accomplishing various operations on an aircraft was a learning experience, as I wished to become an astronaut. This kind of work is referred to as "multi-tasking", requiring qualifications similar to those required by an astronaut. Experience as a jet pilot is useful for tasks in the International Space Station, e.g. manipulating the robot arms.

The T-38 is a two-seater jet, in which multi-tasking can be divided between two pilots onboard: one maneuvering the aircraft and the other performing other operations. When all the tasks are divided, the educational effect of multi-tasking may be reduced. However, this division of tasks creates a new aspect of "coordination" or "teamwork" toward a complete set of tasks. Task division will also reduce the stresses and fatigue each pilot suffers.

Personally, I usually assume all the tasks during the first two sections of flight except for takeoff and landing, while for further sections, the partner pilot on the front seat assumes part of the tasks. I have found this method helps me retain sufficient concentration for safe flight.

I have discussed relatively general matters, basically because I encountered nothing out of the ordinary during flight training in April and completed it successfully and peacefully. Should any failure occur in one of the devices in-flight, that would be a good reason to report it here in an article. That concludes the article for now on T-38 flight training.

Thanks a lot for reading.